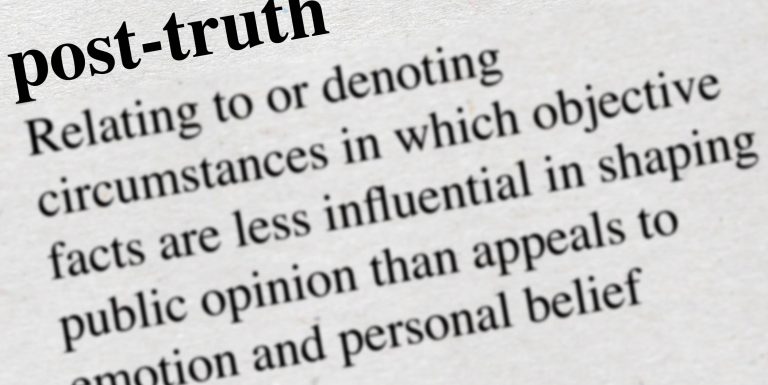

In recent years, discussion around intentions has grown significantly. In evangelical circles, there have been many views of how the intentions of the divine author and the human author interact. In some senses, these fall along a spectrum from seeing the intentions as totally separate, through to completely identical.

It is worth outlining what is meant by the human author’s intention. It can be very easy to overstate what is being said. This has caused many to mishear or talk past the other side. For instance, it would be ridiculous to claim we can infer everything about the author from reading what they have written. We cannot know their background, their psychology, even the time they wrote, unless we are supplied with it. But we can pick up enough to infer the intention of the author. It does not take knowing everything about the engineer to understand what the train departure board is intended for. You may not know everything about this essay author, but you get the idea. We are given what we need to recognise the intention, understand its meaning, and respond. When it comes to the Bible, we can say the same. For instance, if we were to read Jeremiah, we would find that we are given enough information to understand his message and respond to it.

Speaking of Jeremiah, this book is useful in seeing how the human and divine author’s intention interact. God says to Jeremiah that He has put His words into Jeremiah’s mouth.[1]Jeremiah 1:9 For the people, there is no wedge between Jeremiah’s words and God’s words. It is as if Jeremiah has become God’s word incarnated. It is as the people experience Jeremiah, that they experience God’s words. And as they experience God’s words through Jeremiah, they experience God. This idea is not only found in Jeremiah, but it also flows through the Bible, including similar statements from Jesus found in Matthew 10:40, or in John 14.

This raises another aspect of the relationship between human and divine intention for us – the part of placing a book into the Biblical canon. It is reasonable to assume that some authors expected their writing to be canonical. But we cannot say that all the authors knew how the final canon would look – that is something that must be credited to the divine author. A book being placed into the canon means that it is divinely intended to be read alongside other books of Scripture, according to the order of the narrative they create. It is simply not enough to say that God spoke Deuteronomy and Jeremiah, we must go further. We have to say that God spoke Deuteronomy and then Jeremiah. There is an order to the canon, an order that is crucial for reading the Bible. This progression changes how you think and read the Bible. The promises and curses found in Deuteronomy, for example, are solidified by later events. In fact, even by the time we get to the end of Jeremiah itself, we see that the prophecies were definite, credible, and true as we come to the end of the book. This does not change the intention of the author of the book, but it does add more weight to that intention. God says more than the individual authors may have known, yet he does not contravene what the authors wrote and intended.

The timing of communication acts matters. Peter Leithart expresses this idea with an illustration of a shooting.[2]Leithart, Peter, Deep Exegesis: The Mystery of Reading Scripture (Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press, 2009) At 10am an assassin shoots a man. At that point the event is a ‘shooting’. Sadly, a few hours later, the man dies. The shooting, placed into this line of events, has now become a ‘murder’. The way we think about prior information changes as it is placed into a timeline of events. The event itself has not changed, but the canon is placed into changes the way we think about it.

In Jeremiah’s case, what was an open event has now closed. The warnings of judgement are now reality and so are seen as proven and trustworthy. This does not change Jeremiah’s intention, but it has developed and been made more precise. This is the point made and used by the author of Hebrews in Hebrews 8.

The implications of this are worth considering. While Isaiah alludes to Moses, this does not mean the divine intention in Exodus to think of Isaiah. That would be too much to infer. Yes, God knew that Isaiah would write what he wrote. But “intention” is not synonymous with “mind”. Instead, as we read Isaiah, we are to see the canonical connection, and read in the order the narrative created. To argue that God’s intention is the same as God’s mind is to muddy the waters. To say that “because God will say “I AM” later in Scripture, there must be more meaning to Exodus” is confusing at best. Yes, God has a unified plan throughout salvation history. Yes, he knows everything. Yes, as we read Isaiah, after Exodus, we are given more nuance. But that nuance does not change what Moses has written, or his intention in writing. The communication event has not changed, and so we should not artificially read things into the text. The point of what Moses has written, the intention of it, has not changed.

So where do we land with the relationship between human and divine author’s intention? To put it simply, the human intention expresses the divine intention. To say that careful exegesis cannot discover the meaning of the text results in subjective reading. Instead, we should see that the human and divine intention are always aligned, and the divine intention is always in some way (supervening, not contravening) related to the human intention.

Thanks for reading! The above is an essay I wrote on the interplay between the Divine Author and Human Author’s intention. Any feedback greatly received as I continue to think through this topic!

In the words of our Jimmy: hallelujah, amen!